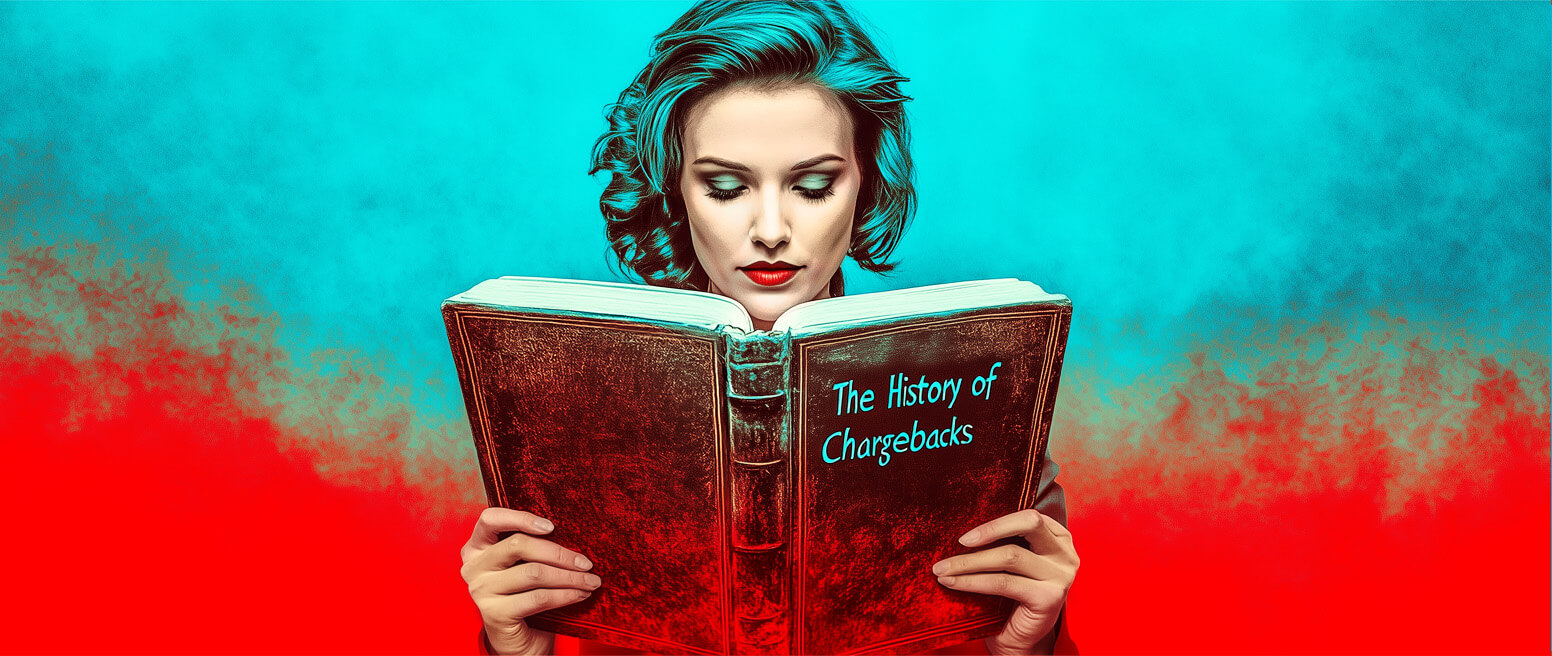

How the History of Chargebacks Helped Shape Commerce as We Know it Today

Cardholders who feel that a credit card transaction is inaccurate or unfair have the option of disputing the charge. This is called a chargeback.

Chargebacks give the bank permission to forcibly remove funds from a merchant's account and return the money to the customer's account. As such, there are only a few legitimate reasons to file chargebacks:

However, in the age of digital commerce, we’re seeing more and more chargebacks filed without a valid reason. In fact, our research shows that more than 60% of the 615 million chargebacks filed in 2021 will be these “friendly fraud” cases.

Learn more about friendly fraudHow did this happen? What is the history of chargebacks, and how did something created to protect consumers from fraud become a tool to commit fraud instead? Let’s find out.

Recommended reading

- What Happens When You Dispute a Transaction?

- Provisional Credits: Here’s Everything You Need to Know.

- Here are the 7 Valid Reasons to Dispute a Charge

- What Happens if You File a False Chargeback Claim?

- A Step-by-Step Guide to the 2025 Chargeback Scheme

- A Step-By-Step Guide to the Chargeback Process in 2025

Part 1: Before Chargebacks

The history of chargebacks is irrevocably linked to the history of credit cards themselves. So, let’s start by outlining how credit cards, payment fraud, and fraud prevention first became concerns.

First Reported Credit Identity Theft

1899

The basic concept behind credit cards—using something of no intrinsic value to facilitate a financial transaction—is almost as old as commerce itself.

By the late-19th Century, many merchants issued credit coins and/or charge plates to regular customers to extend credit. Public transportation companies, for example, issued passes that allowed holders to ride on credit, then settle up at the end of the month.

In 1899, an enterprising man observed another man tossing his "credit card" in the trash. Retrieving the card, the imposter was able to use it for a month, running up a huge tab on the original owner's bill, thereby creating the first recorded case of credit card ID theft.

Charg-It

1946

Several department stores and gas stations issued their own proprietary cards throughout the first half of the 20th Century. Like modern-day department store cards, they were accepted only by the issuing merchant, who considered them a way to boost customer loyalty.

A New York banker named John Biggins took the idea one step further by creating the Charg-It card, which allowed credit at multiple local merchants. This card was only available to customers of Biggins' Franklin National Bank.

BankAmericard

1958

Other banks took up Biggins' idea. There was a significant difference between these cards and modern credit cards, though.

Back then, accounts had to be paid in full at the end of each month. The year 1958 saw the debut of BankAmericard, issued by Bank of America, which was the first bank card that offered revolving credit at any participating merchant. This is notable in the history of chargebacks, as BankAmericard was the forerunner of what we now know as Visa. MasterCharge—which would become Mastercard—showed up a few years later.

It should be noted that instead of waiting for customers to decide if they were interested, BankAmericard jump-started the process by mailing 60,000 cards to unsuspecting customers. This blind mass-mailing technique was standard practice for the first few years, resulting in many credit cards going to people who typically wouldn't qualify for a credit card. Not surprisingly, trouble followed.

Part 2: Where Did Chargebacks Come From?

So, it’s the 1960s, and credit cards are finally starting to hit the market. There’s a problem, though: the often-cavalier way credit cards make their way into consumers’ hands means that credit card fraud is growing fast.

The system was on track to become unworkable. To protect consumers, and make payment cards viable in the long term, something had to be done. This is where we find the origin of chargebacks as a concept.

The Truth in Lending Act

1968

Bank cards had gone global, but they still hadn't gained the widespread acceptance the networks were hoping for. US customers, in particular, were suspicious of this newfangled payment method.

The Federal Reserve Board alleviated some of these fears with The Truth in Lending Act of 1968, or TiLA. This required lenders to provide customers with clear loan cost information. This included the introduction of concepts like annual percentage rate (APR), loan term, and total costs to the borrower.

Now, cardholders were guaranteed to have informed consent before agreeing to the terms of a loan.

Magnetic Stripe Technology

1968

TiLA helped protect consumers against predatory lending. Rampant credit card fraud was still an issue, though. This problem drove banks to find a faster, more secure way to process transactions.

IBM introduced a technology that allowed cardholders' information to be encoded on a magnetic stripe attached to the plastic card. A multiple-day time lag for verifications was reduced to a matter of seconds. While this technology took many more years to become standardized, it was a great step forward for fraud prevention technology.

Section 75

1974

One provision in the Consumer Credit Act of 1974 — Section 75, to be specific — offers buyers legal protection in the event that a transaction involves the purchase of faulty, damaged, or missing goods.

Purchases of more than £100 in value, but less than £30,000, are eligible for Section 75 protection—debit card purchases are excluded. If found liable, either the merchant supplying the faulty goods, or the consumer’s credit issuer, may bear responsibility, and be required to reimburse the buyer.

We need to emphasize that chargebacks are not the same as Section 75 claims. Chargebacks are voluntary protections extended to consumers by payment networks like Visa and Mastercard, while Section 75 is a legal right.

Fair Credit Billing Act

1974

Even with new safety technology and regulations in place, people still worried that their card could be lost or stolen. They could be left stuck paying for unauthorized transactions. There were also fears of unscrupulous merchants inflating prices or tacking on transaction fees after the fact.

The Fair Credit Billing Act of 1974 attempted to address these issues by creating what we now know as a chargeback. This is where the history of chargebacks begins.

The chargeback option reassured consumers in two ways. First, it strictly limited their liability in the case of fraud. At the same time, it helped keep merchants honest by giving cardholders the ability to fight back against deceptive practices.

Electronic Fund Transfer Act

1978

The next step in chargeback history is the Electronic Fund Transfer Act. This legislation provided debit card fraud protection that was similar to that of credit cards. However, those protections are not as comprehensive as for credit cards.

The EFTA does limit liability in the event of fraud, but this only applies if the customer reports the incident within the allowed time frame. Also, the regulation does not stipulate repayment of any money withdrawn from the customer's account.

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA)

1986

The CFAA amended the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984 to include criminal penalties for various computer-related cybercrimes. The CFAA prohibited the unauthorized access of protected computers and files, and made it illegal to steal passwords, sell illicitly-obtained data, or install ransomware on protected devices.

Congress enacted the CFAA in response to the proliferation of computer usage in the 1980s. Prior to the Act, no federal law explicitly addressed cybercrime. The law was the first to impose criminal penalties upon individuals who participated in fraudulent or illicit computer-related activities.

Part 3: The Rise of eCommerce

Note that the next event on our timeline happens nearly four decades later after the EFTA. The entire way we shop, work, learn, and communicate was completely upended and revolutionized during that time.

eCommerce came to be the dominant sales channel for millions of consumers. The chargeback system, however, remained essentially unchanged.

The Credit CARD Act

2009

Signed into law in May of that year, the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure (Credit CARD) Act of 2009 established a slew of consumer protections. The act guards American borrowers against unclear or deceptive contract language, retroactive interest rate hikes, unfair billing arrangements, and excessive fees.

The Credit CARD Act also established the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, or CFPB. This is an independent federal agency that supervises and examines financial institutions to ensure that they are in compliance with the law. One of the CFPB’s priorities, for instance, is to protect consumer cardholders’ access to chargeback protection, in line with the FCBA of 1974.

Friendly Fraud Becomes a Problem

2010

In 2010, accounts of unusual chargeback activity began to be reported by major news networks. Friendly fraud was becoming a serious problem for the first time.

The reasons for this are manifold. But, the main factor was the onset and eventual dominance of eCommerce. In the last decade, friendly fraud became the leading cause of chargebacks, with no signs of an eventual slowdown.

Data Breaches

2013

Between 2013 and 2015, a mere seven data breaches exposed personal information from over 6 billion consumers. That doesn't include the billions of other records exposed in other hacks.

High-profile breaches of companies like Sony, Target, and Equifax became global news stories. Of course, there’s no guarantee that a breach will ever lead to an individual’s data being used by a fraudster. But, in many cases, these breaches gave criminals access to usable information, which was then used to complete counterfeit transactions.

EMV Liability Shift

2015

Consumers demanded more protection from fraud. In response, card networks in the US began shifting from magnetic stripes to EMV "chip" cards to protect their interests, as well as those of their customers.

The chip technology in EMV cards is more secure. However, it required merchants to invest in new card readers. As an incentive, the networks began shifting fraud liability to merchants who didn't upgrade. Essentially they were telling merchants: "You can use old equipment, but if a fraudulent transaction happens, we'll hold you responsible.”

Visa Claims Resolution

2017

Recognizing that the legacy chargeback system wasn't working, Visa rolled out a new dispute process, called Visa Claims Resolution (or VCR). The new procedure sought to close profit-absorbing loopholes, reduce false claims, and improve the customer experience. For merchants, this theoretically meant fewer chargebacks filed. It also meant less time available to respond to the chargebacks that did get filed though.

Mastercard began implementing its own initiative later that year. A similar program to VCR, Mastercard's changes were to be rolled out in phases through 2020.

GDPR

2018

The EU General Data Protection Regulation is designed to protect consumer privacy. It limits the way companies are allowed to use and store customer data.

The GDPR promises to reduce the amount of personal information available in the event of a data breach and limits companies' ability to hold on to said data in the interest of fraud prevention. The full effects of this regulation remain to be seen, but it will impact the history of chargebacks over time.

Acquisitions & Consolidation

2019

Mastercard acquired Ethoca, and Visa acquired Verifi. These acquisitions vastly altered major card networks’ approaches to fraud, including friendly fraud. They provided merchants with advance chargeback alerts and improved dispute resolution processes.

These programs are not guaranteed to eradicate chargebacks or their fees. However, they can still be very helpful to merchants looking to prevent chargebacks.

Covid-19

2020

In 2020, the global pandemic drove everyone indoors…and online. The resulting spike in online activity meant eCommerce figures went skyrocketing into the atmosphere. At the same time, this naturally led to a monstrous surge in cybercrime, friendly fraud, and chargebacks.

Millions of cardholders who saw travel plans and reservations canceled decided to file chargebacks. Others, aggravated by slowdowns resulting from supply chain and logistics hassles, filed chargebacks out of frustration.

The Future of Chargebacks

We’ve gone over the state of things as they are now and explained the history of chargebacks, but what about the future? Can we expect any relief from friendly fraud? How about lower costs and fees? Is there anything we can do to better mitigate and recover from the losses we’ve incurred?

Based on our research, let’s have a look at some of our chargeback predictions:

Safeguard Your Financial Future

So, that's the history of chargebacks in a nutshell. eCommerce is constantly evolving, though, and chargebacks aren’t going anywhere. To combat this, merchants should employ intelligent chargeback management strategies that are flexible enough to identify new trends and techniques, counteract new technology, and adapt to a changing landscape.

No one understands this better than the experts at Chargebacks911®.

Our transparent, end-to-end solutions go beyond prevention. With Chargebacks911 in your corner, you can pivot from defense to offense and see genuine revenue recovery and future growth.

Whatever you need to fight chargebacks, the solution is just a click away. Contact us today for a free demo.

FAQs

When were chargebacks introduced?

Chargebacks as we know them today were introduced by the Fair Credit Billing Act of 1974. The FCBA gave consumers who held open end credit accounts — like credit cards and charge cards — the right to dispute fraudulent transactions and rectify merchant billing errors.

What are the three types of chargebacks?

Broadly speaking, there are three types of chargebacks: merchant error chargebacks, criminal fraud-related chargebacks, and friendly fraud. Chargebacks initiated by consumers in response to merchant errors like billing mistakes or missing goods are legitimate. Chargebacks that reverse unauthorized transactions are also legitimate, even though the transactions themselves were not. However, chargebacks are considered fraudulent when they are filed by consumers against legitimate transactions; a practice that is commonly known as friendly fraud.

Why do companies hate chargebacks?

Chargebacks are universally unpopular among merchants because they result in lost inventory and out-of-pocket penalties. Unlike a refund, which occurs when purchases are returned and transactions are reversed, a chargeback causes the merchant to suffer a unilateral loss. To add insult to injury, merchants are often assessed steep fees, ranging between $20 and $100, for every chargeback they incur.

Do banks really investigate chargebacks?

Yes. Banks employ fraud examiners and other specialists who analyze chargebacks for signs of unauthorized activity. Banks actively engage in the dispute process not only because they are legally required to do so, but also because they have a vested financial interest in preventing fraud losses.

Are chargebacks illegal?

No. Legitimate chargebacks can be filed against unresolved merchant errors or charges incurred as a result of unauthorized activity. Chargebacks are potentially illegal, however, when they are used by consumers to perpetrate friendly fraud. This illicit practice occurs when consumers dispute legitimate transactions because they experience buyer’s remorse or wish to get a product “for free.”